Did a friend forward this to you? Join for free by clicking here.

“What if I can’t win a single game and walk off the court 0–6, 0–6?”

“If I don’t win, it means I’m unworthy. ”

“I’m feeling a bit off today so that must mean that I’m not going to play well. What’s the point in trying?”

Have you ever had thoughts like this? I’ll be honest. I have. And, if most tennis players were honest, they’d also admit that they’ve indulged in thoughts like this.

But what’s the issue? They’re just thoughts, right? Just little things floating around in our heads. How can they be that impactful?

“Think positive!” is a glib retort that is often offered when players profess to be engaging in thoughts like this. Or, “Don’t engage in it. If you have a thought like that, just tell yourself to stop!”

This approach not only ignores the underlying issues with these thought patterns but gives an overly simplistic way of countering them.

To understand the power of thoughts, and how cognitive distortions impact us in our tennis (and even our life), it’s important to first understand the cognitive-behavioral model.

It’s All Connected: The Cognitive-Behavioral Model

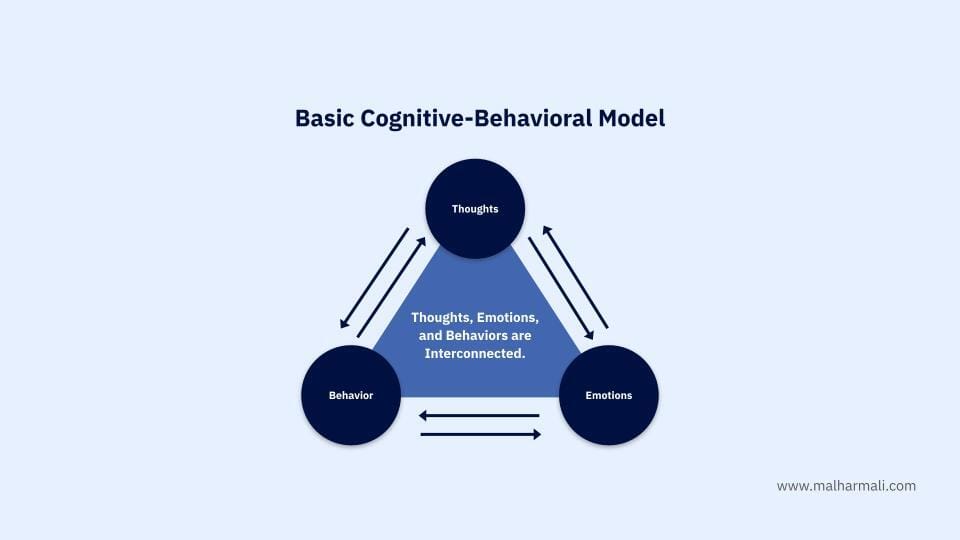

Aaron Beck, the father of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, was one of the first psychologists to point out the intense relationship between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Along with other pioneers of the field, therapists focused on helping clients understand that thoughts, emotions, and behaviors were powerful factors in everyday life (and in our case, sports), and if we learned to test and manage these three facets, we could learn to have more enriching and fruitful lives.

Have the thought that, “I’m a piece of shit. I’ve double-faulted three times this game already,” and that can lead to sadness, upset, or even anger depending on deeper schema.

Have the thought that, “I’m anxious and nervous, but that just means that my body and mind are getting ready to compete well and fight hard in the upcoming match,” and notice how your anxiety abates and you are able to perform well.

(N.B.: facilitative interpretation of anxiety and stress is consistently shown to be a differentiator between elite athletes and those competing at a lower level. I wrote about it last week. It’s linked below. Go to the section that compares facilitative vs. debilitative anxiety).

This supposition—supported by decades of practice and research, by the way—, that thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are all connected can be best understood by this simple model below:

We need to understand that they are all connected.

But here’s the problem: many of the thoughts we have on court aren’t deliberate. They pop into our heads automatically, without us consciously choosing them.

These are called Negative Automatic Thoughts (NATs)—quick, reflexive reactions that shape how we feel and act. And where do these NATs come from? They’re often rooted in Cognitive Distortions—deep-seated, habitual ways of interpreting events that aren’t entirely accurate.In other words, NATs are the surface-level expression of distorted thinking patterns that we often aren’t even aware of.

For example, if you’ve struggled to close out a few close matches, you might have the NAT: “I always choke under pressure,” or “I’m going to choke again.”

But if we dig deeper, this NAT is being driven by an underlying cognitive distortion, such as overgeneralization (assuming that past failures mean future ones are inevitable) or labeling (defining yourself as a “choker” rather than recognizing that you’ve just had a few tough matches where you’ve been unable to close it out).

These distortions don’t just affect your emotions and behaviors in the moment—they shape how you train, compete, and even view yourself as a player. They are incredibly powerful. And if left unchecked, they can create a vicious cycle that reinforces anxiety and poor performance. Below all of this are your schema… but we can save that for another day.

Examples of Cognitive Distortions in Tennis

Let’s get specific about certain cognitive distortions. Let me know if you’ve ever engaged in these patterns of distorted thinking. I’m pulling these out of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Made Simple by Seth J. Gillihan and also Chapter 14 in Jean Williams and Colleen Hacker’s Applied Sport Psychology (this chapter is also written by Williams and Hacker).

Distortion #1: Worth Depends on Achievement

I wanted to start with this one because it is probably the most dangerous, impactful, and insidious of distortions. Athletes engaging in this distortion are constantly bobbing their heads above water in stormy seas. Every time they manage to win a match or get a few wins under their belt, they are able to come up for air. When they lose? It’s like they’re swallowed and carry the weight of the ocean upon them. Put another way, athletes who derive their self-worth as human beings solely based upon wins and losses in their competitive domains are setting themselves up for anxiety, burnout, and a terrible relationship with their sport. In my experience, if this is a distortion that you engage in as a tennis player, it’s probably also a distortion that you’ll engage in with other facets of your life. For example, “I’m only worthy if I make 6 figures and have a prestigious job.” Not to give you sob stories, but these are some of the things I’ve struggled with as an athlete (and a human being!).

Your worth is not defined by winning or losing. Nor is it defined by how shiny your business card is. If you’re finding yourself engaging in this distortion, it’s important to take pause. This can be difficult because I know that athletic identity weaves into this. If tennis is your life, or is the only thing that defines you, then, yes, it can be easy to fall into this trap.

Distortion #2: Catastrophizing

Have you ever been broken in the first game of the match and thought, “Crap. I’m going to lose.” Maybe you’ve lost a close set and then had repeated thoughts like, “Now the match is over. I can’t come back from this.” Perhaps you’ve had consistent back issues, and at the first niggle while warming up for a serve, your psyche latches onto, “I’m going to injure my back again.”

This is a cognitive distortion called catastrophizing. Something happens, and all of a sudden, you jump to the worst possible conclusion. You fixate and ramp up what could potentially happen and turn that dial all the way to 10.

Instead of staying present and trying to get the break back, or figuring out if you need to change tactical approach after losing the first set, or taking care to warm your back up properly, you’ve—inadvertently—taken your conception of the event and ratcheted it all the way up.

Distortion #3: All-Or-Nothing Thinking

This is the perfectionist trap. And if you’re a perfectionist, you’re likely to engage in it.

It can be summed up as: if it’s not perfect, it’s worthless.

I hope you can see how damaging thinking this way can be.

Ever walked off the court after a loss and thought, “That was a complete waste of time”? Or won a match but still thought, “I played terribly, so the win doesn’t count”?

This kind of thinking makes every match a referendum on your worth as a player, with only two possible outcomes—success or failure. Here’s why this is dangerous: Tennis isn’t black and white. You can play well and still lose. What if you play someone who is way more skilled than you? And you can play badly and still win. That’s just the reality of competitive sports.

You can improve your serve dramatically but still double-fault a few times. If you only allow yourself to feel satisfied when you’re flawless, you’re setting yourself up for constant disappointment. Thinking in this way is no fun. Worse, it’s actively damaging your relationship with tennis.

Distortion #4: Mental Filtering

This is where you zoom in on the negatives of your performances while completely ignoring the positives. If something great happens, or if you have a decent result, and you’re solely fixated on the negative things that happened, then, yeah, you’re engaged in this type of distortion.

Ever walked off the court after securing a hard-fought win upset that you double-faulted nine times? Instead of focusing on how you managed to stay strong, task-oriented, and present when it counted, you spend post-match being distraught by the number of your double faults. You fixate and beat yourself up over it for longer than is healthy.

An important note of clarification here: of course, you should reflect and critically assess your matches and performances. But being brutal and cruel to yourself is perfectionist thinking. And it isn’t helping you perform better and your relationship with tennis.

These are but a few distortions that we athletes engage in. If you’ve realized that you’re engaging distortions like this, it’s good. Why? Because realizing them is the first step towards disputing them. And to do so, I’d like to propose Albert Ellis’ ABCDE model.

Albert Ellis’ Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT)

Albert Ellis, along with Aaron Beck and other pioneers, were pivotal figures in the building of modern cognitive behavioral therapy. Ellis developed Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), which is a method of assessing and challenging thoughts and replacing them with more helpful, nuanced perspectives. Practitioners using this model apply variations of the ABC model to help individuals address the distortions in their thoughts and beliefs. We’ll expand ours slightly to use the ABCDE model.

Here’s how it works, applied to an activating event of you being nervous and anxious at the start of the match and as a result, losing your first service game to love.

Note here that sport psychologists or sport psychology practitioners sometimes advocate “thought stoppage” techniques, which are exactly what they sound like. Asking athletes to create cues or behaviors that get them to stop the negative thoughts that they’re engaging in. However, consistent research in psychopathology shows that thought-stopping techniques create a rebound effect, especially under cognitive load, where the individual trying to force the stoppage of the thought actually experiences it more often (see Koster et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2022). The jury is still out on techniques that go a little further like asking the individual to stop the thought and replace it with something more positive. However, this is definitely not what the early cognitive therapists advocated for. Rather, a running theme in cognitive therapy is to treat thoughts as hypotheses which can be tested or suppositions that can be critically assessed.

This is where REBT and the ABCDE model comes in!

Activating Event

This is the situation that triggers the reaction based on the belief. In this case, you step onto the court for an important match, and you’re feeling jittery and tense. Your nervousness has impacted your confidence and you end up double-faulting three times. Before you know it, you lose your opening service game without winning a point.

Belief

This is your immediate read or interpretation of the event, and it often contains a cognitive distortion. If you’re prone to catastrophizing, you might think here: “Shit. Now I’m going to lose this match. My serve isn’t here today. It’s going to be a disaster.”

Consequences

Your belief—influenced by cognitive distortions—leads to emotional and behavioral consequences. If you believe you’re doomed after one bad game, your anxiety is going to increase, your confidence will plummet, and you could tank, be upset, or even play tentatively. Your focus shifts from staying task-oriented and in the actual match to the deranged running commentary you’re continually tuning into. Think back to Attentional Control Theory, which we’ve covered before (Eysenck et al., 2007).

Disputation

This is the most important step! It’s where we challenge the distorted belief. Instead of passively accepting and latching our hooks into your thoughts, you ask yourself:

Is it really true that losing my first service game will mean I’ll play badly for the whole match?

Do pro players sometimes lose their first service games but rebound to play well? (Hint: yes)

What would I tell my friend, husband/wife/partner, or maybe even my child if they were having similar thoughts in a similar situation?

Effective New Belief

The final step is adopting a more helpful perspective that leads to productive emotions and behaviors. Instead of feeling hopeless, you refocus and tell yourself: “This match is long. Tennis is the only sport without a time limit! One bad game doesn’t define how I’ll play the rest of it.” With this shift, you can loosen up, stay engaged in the present moment, and give yourself a much better chance of playing the sort of tennis that will leave you happy as you walk off the court—win or lose.

Use This Sheet

If distorted thinking patterns are holding you back and standing in the way of great performance and a healthy relationship with tennis, the answer isn’t to ignore them or mindlessly “think positive.” Instead, our goal is to recognize, challenge, and replace these thoughts with perspectives more aligned with reality.

I’ve made an ABCDE model worksheet available for you to download at no cost. Work your way through your distorted beliefs. These are the kinds of sheets sport psychologists and sport psychology practitioners use with their clients.

Negative thoughts will always arise, but how you respond to them makes all the difference. The best players aren’t free from doubt or frustration—they’ve just trained themselves to handle it better.

References

Wang, D. A., Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2020). Ironic effects of thought suppression: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(3), 778–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619898795

Disclaimer: I am not an Association of Applied Sports Psychology CMPC, certified sports psychology practitioner, nor am I a licensed mental health counselor, PsyD, or clinical PhD. I am pursuing a master’s in sports, exercise, and performance psychology, and I am a sports psychology practitioner-in-training. I have over 20 years of experience in tennis, including playing, coaching collegiately and with professional players, along with club management experience as a director of programs. I am certified by the Professional Tennis Registry and am a member of Tennis Australia. My aim is to bring the best information to tennis players around the world so that you can apply it for long-term improvement—but sometimes I will make mistakes. If this is your area of research or expertise, and you feel I’ve misunderstood something, please get in touch with me and if required I will happily issue a correction.